Northern France has been a mixed bag for the British over the years. From the brutal reality of the western front in the First World War, to the high life of the baccarat tables in Le Touquet in the 1930s, to becoming a day tripper’s mecca – thanks to Eurotunnel – in the 1990s. Next year though, British interest in northern France, and its capital Lille, will centre firmly around the Rugby World Cup.

The city of Lille has been fiercely fought over for a thousand years. A compliment to Lille perhaps but one that was paid in blood by its citizens as conquerors from Spain, nearby Flanders, the Burgundian empire and the German Empire, twice, all occupied Lille over the past millennium.

Its current landlords, the French, moved in in 1667, and people living in Lille today seem pretty content about that. Yet Lille isn’t French, not really. Not by any of the stereotypical measurements of French-ness at least. They drink beer here for a start, and lots of it.

Lille is one of France’s nine host cities for next year’s Rugby World Cup. And it’s probably the one we know least about, particularly from a rugby perspective.

Fans attending matches at next year’s tournament will know what rugby paradise lies in wait for them in Marseille, Toulouse and Bordeaux, while host cities such as Nantes and Saint-Etienne proved their credentials when staging matches at France’s magnificent Rugby World Cup in 2007. Lyon meanwhile boasts its own Top 14 team. And Paris is, well, la belle Paris. That leaves Nice in the south-east and Lille in the north-east as the two outlier host cities.

Yet it’s worth getting to know Lille, especially for British rugby fans as England will play half their group matches (against Chile and Samoa) here, while Scotland face Romania in the city too. In a true show of faith in Lille’s ability to throw a party, the hosts France are even playing Uruguay in Lille. It’s also the nearest port of call for UK rugby fans who develop FOMO during the first two weekends of the World Cup and fancy a bolt across the channel when England and Scotland play in Lille (September 23 – October 8). By Eurostar, Lille is just an hour and 22 minutes away from St Pancras, so it’s eminently do-able.

And it’s not just the beer-swigging locals that surprise when you first arrive in Lille. Nondescript and industrial were my expectations. Instead, Lille is bustling with energy, clad in medieval architecture and boasting an old town that teems with bars and restaurants, especially the charming Estaminet-style bistros which Flanders is famous for. It feels more like Ghent or Bruges (which are both less than an hour’s drive away). Such is its Flemish influence, Lille is even jokingly referred to by the locals as the ‘Capital of Flanders’. So it’s a mix, and culturally richer for it.

Its cuisine is Flemish in influence too. Yet the city’s chefs seem to be locked in a culinary contest to out-do each other in re-interpreting local classics with modern twists, and the results can be spectacular.

When the Rugby Journal arrives, our first visit is to the central train station where a re-purposed TGV has been turned into a travelling rugby circus that will soon depart Lille to start a promotional tour of France. One of its passengers is ‘Bill’ – also known as the Webb Ellis Cup – which is displayed inside one of the train’s carriages for fans to walk past and take photos with. Other carriages include a scrum machine to test your pushing power, and a virtual-reality booth that places you in the middle of a rugby match at the Stade de France.

Lille’s central station connects with the Pierre Mauroy stadium where matches in Lille will take place. It’s a 25-minute train trip, which seems long for a relatively small city but is quicker than the one from central Paris to the Stade de France.

We aren’t going to the stadium just yet however, we’re going to conduct some equally important research about where to eat in Lille. Our first stop is called Babe, a restaurant where both the local fire service and the police have lunch, a positive sign surely; unless you need to call upon them this afternoon. Babe’s menu is extremely appealing for eaters with appetites, but you won’t leave feeling light on your feet. The pin-up star is their Osso Buco, a plate of gooey bone marrow, with orange and saffron garnishing, with the marrow set alight by your waiter upon its arrival. It’s a spectacle, and tastes just as good. There’s also an exquisite octopus dish, as well as a burger boasting beef from Hereford no less. If you’re in Lille next year for your World Cup fix, Babe is a must.

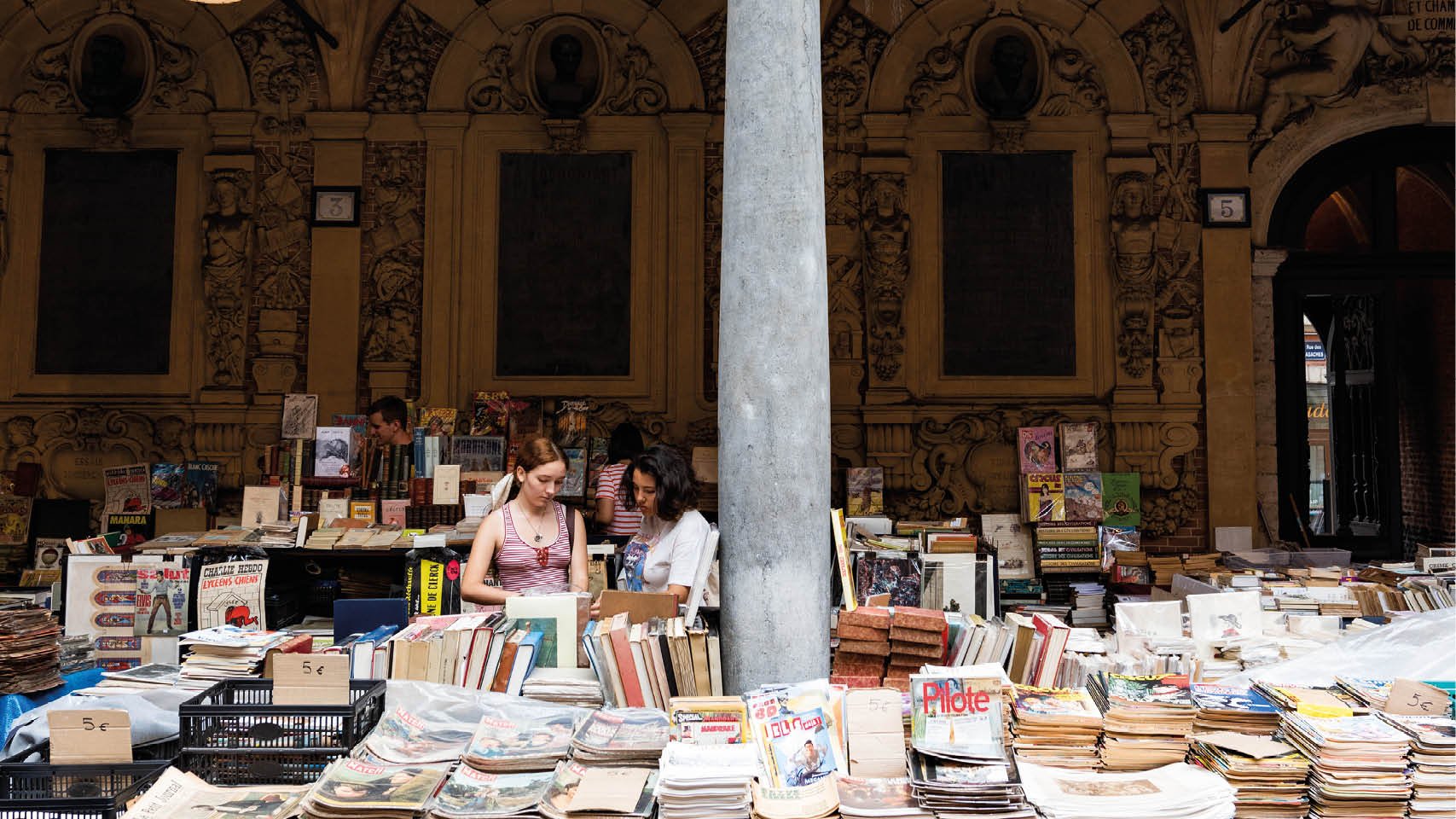

Lille is the beer capital of France and the region is home to 2,000 of France’s 3,500 breweries. It’s those Flemish roots again. You can get good wine in Lille of course, but you have to seek out dedicated wine bars, of which there aren’t many. A beer tour, which doubles as a city tour, is in order. Our guide Aurélie, makes our first stop the Grand’Place, Lille’s main square, which is flanked by impressive Flemish architecture from the Middle Ages with bistros and bars that jut out from under arcades. This is where everyone in Lille meets. If you’re planning a day of sight-seeing, or beer drinking, you can’t do better than starting out here. The most striking building is the Old Stock Exchange, composed of 24 identical houses surrounding a cloister. It is unquestionably beautiful. It now hosts a market for second-hand book sellers and acts as an arena for amateur chess players, who can gather a fair crowd at any time of day.

Under the columns that surround the cloister are reliefs in stone which commemorate famous citizens from Lille’s past. Aurélie points out their most illustrious, Louis Pasteur, a chemist who whilst on holiday in 1864 discovered that partially heating his wine was sufficient to prevent it souring, without compromising its flavour. So useful was his discovery for vintners and brewers that the process was named ‘pasteurisation’ in his honour.

Although not a rugby fan, Aurélie is nonetheless excited that her city is hosting matches at next year’s Rugby World Cup, remembering fondly the visit of Welsh football fans for the quarter-finals of Euro 2016 when Wales beat Belgium 3-1, in one of their best-ever performances in a major tournament. Followed presumably, for Welsh fans, by one of their best-ever nights out.

“British people are like us,” she says. “They don’t mind big crowds and everyone cooperates and behaves really well, everyone is friendly. The people here are really welcoming – not because they are grateful for the attention but because people really suffered after industrialisation slowed down in Lille. Northern France was overlooked for a long time, now it’s trendy again.”

Aurélie’s tour then takes us past the UNESCO World Heritage building that is Lille’s town hall belfry, a Gothic-looking structure, over 100m high, that offers the best views of the city. We don’t scale it however, as we have beer to drink.

Aurélie steps off the cobbled streets and enters what looks like a townhouse. Indeed, it is a townhouse but one that’s been re-fitted as a micro-brewery. After the usual explanations of how the beer is made, the tasting begins and it’s definitely been worth the wait. All sorts of flavours pop out of different bottles and it becomes increasingly important to pay attention to the alcohol content. In Lille, some beers weigh in at fourteen per cent ABV.

We finish the tour at a street corner where two friendly bars are about to open for their evening’s trade: La Capsule and Le Bar Braz. This junction feels like a must-visit during the Rugby World Cup. Not only does the whole scene – a cobbled street called Rue Des Trois Mollettes dividing two bars with pastel coloured houses on either side – feel like a throw-back to what life might have been like a century ago, but the publicans allow drinkers to slide seamlessly from one bar to another so you can catch up with friends drinking over the road. Mostly though, drinkers convene happily in the middle of the road. Not many cars come this way. In such an atmosphere, it’s not hard to imagine yourself in the afternoon sun of next September striking up a rugby conversation with a few locals about Antoine Dupont’s genius, Melvyn Jaminet’s suave running, or Romain Ntamack’s suaveness in general. They might not be rugby-mad in Lille but they enjoy supporting the French national team.

Night spots in Lille are authentic. One that attracts us seems to have been drawn by Edward Hopper in a happy mood. A big glass window reveals an orange-lit bar scene set amongst bookshelves with saloon-style enclaves. Dancers twist and glide in front of the bar. And one reveller gives us a brief history lesson. “In the south, it was the Republicans who liked rugby,” he broadly surmises. “In the north, Catholics liked football, so it’s mostly football up here. Lens are the biggest team.” And what about the Rugby World Cup? “Yea, yea, it will be fun.” Not an altogether convincing tribute but at least the tournament is on the radar.

The next morning we head out from Lille to the small town of Arras. For most of the First World War, Arras was six miles behind the western front’s front line, and for that privilege, it was frequently shelled by German artillery. Arras is just 45 minutes south of Lille, but far more French in feel than the Flemish Lille. Such was the damage wrought on this handsome medieval town that, after the war, it was decided Arras should be re-built to look precisely as it had done in 1914. And having almost lost their town, the residents of Arras have steadfastly preserved its medieval character ever since. The cobbles and colonnades around the town square make it the perfect spot for whiling away an afternoon at one of its many cafés or bars, with a glass of wine and a plate of charcuterie meats and cheeses to hand. Good wine is back on the menu now we’re in the provinces. After a glass or two, it becomes easy to place yourself in 1916, as an allied soldier having a drink whilst on leave from the front. Just add a few smouldering buildings to your mind’s eye and you’re there. In Arras, you can be confident that the outline of your horizons would have been very similar to how it looks now.

The next day, we’re able to indulge further in First World War escapism by visiting a nearby museum, the Wellington Quarry, which tells the story of how, in 1916, a small group of New Zealand soldiers dug a network of tunnels – twenty metres underground – to connect disused chalk quarries together, just outside Arras. Their efforts allowed 24,000 troops to live underground in preparation for a surprise assault on the German lines which took place in the spring of 1917. At the time, it was the biggest underground project ever carried out by Allied troops and the evidence of their time living in the quarries has been impeccably well preserved for everyone to appreciate.

The tour itself – which starts with an elevator ride underground – has been so well crafted that even your safety helmet has been designed in a First World War style. The helmet also doubles as your audio guide, with speakers just behind your ears softly piping up when old footage of life in the quarry is beamed onto chalk walls as you walk around. There’s plenty to take in visually too, with evidence of life in the quarry having been left untouched since the day of the attack on the German lines. Tins of empty Turnwright’s Toffee Delights lie about the old canteen next to old tins of Oxo cubes; whilst the wooden beds soldiers slept on have been re-built and their left-behind belongings have been placed around their old quarters.

It’s a first-class museum experience in an area where excellent military excursions are to be found everywhere. Our next stop is another of those: the Newfoundland Memorial Park, on the front line of what was the western front. It’s a part of the line from where soldiers went over the top during the Battle of the Somme. The ground here has been undisturbed since the end of the war, allowing visitors to see the trenches on both sides and where guides can even point out trees that were also standing in 1916. Seeing the lay of the land as it was, gives you every possible chance of placing yourself in those soldiers’ shoes. It’s an experience which sucks you in.

After our fascinating tour of the trenches, we re-set the sat nav and head north to the Opal coast and Le Touquet-Paris-Plage.

The quirky seaside town of Le Touquet is Eddie Jones’s and England’s World Cup home. They could be here for anything from six to nine weeks, depending on how well they do. That alone will make it a pilgrimage for many England fans intent on getting some rugby player twitching done amongst the small streets of Le Touquet. But it is a worthy destination in its own right, and at only two hours from Lille and three hours from Paris, very do-able as a day trip or a one-night excursion. Le Touquet has charmed French and British holiday-makers alike for 100 years. Having risen out of the barren sands of the Opal coastline, the town has a unique character with acres of pine trees leading to wide, ambling boulevards that merge with a picturesque town, the beach and the Atlantic ocean.

Its buildings reflect the height of pre-war elegance and sophistication giving it a time-capsule quality. The time it captures is between the 1920s and 1930s, when Le Touquet was the weekend escape of choice for Britain’s ‘smart set’, a group spearheaded by Noël Coward. Other famous Brits of that era known to spend time in Le Touquet were Winston Churchill and PG Wodehouse. These days French President Emmanuel Macron is a frequent visitor, as his wife’s family owns a house near the main street, Rue Saint-Jean.

The hallmarks of Le Touquet’s heydey can be seen wherever you wander. There’s the ultra-smart and fashionable Westminster Hotel where Sean Connery is said to have signed his first contract to play James Bond. Then there’s the Casino Barrière on which Ian Fleming based the casino in Casino Royale, and where the future King Edward VIII [the abdicating King] was partial to a game of baccarat.

There’s also the sophistication of Le Touquet’s two oldest golf courses, La Mer and La Forêt, which provide a gorgeous mix of man-made landscaping with the natural advantages of a seaside town, and views to go with it.

For Eddie Jones and England, these aren’t, so much, why they chose Le Touquet. Although golf does tend to go down well with rugby players the world over. England like the simplicity of Le Touquet, further underlined by Eddie’s decision not to put the team up in the luxurious Westminster Hotel, and to instead book the Holiday Inn (yes really) at the back of town.

When the Rugby Journal arrives, it quickly becomes clear why. Le Touquet’s Holiday Inn is set back from the town’s main drag. It’s hardly exclusive, but it is slightly hidden away. It is bright and airy, and although it has a 1990s feel to the décor, it also captures the unmistakable feeling of being on a holiday, a 1990s holiday. There’s a games room with a pool table, arcade games including Pacman, even a pinball machine. There’s also a small swimming pool and a patio area which connects the private spaces just outside each room, making them, well, not so private. If you’re an England player staying on the ground floor next year, the opportunities for getting pranked by your team-mates are endless.

Furthermore, the training pitches England will use are just a ten-minute walk away, through pine trees and sleepy back roads. There’ll be no loading and unloading onto team buses to get to training, giving players more time and space, and reducing the bubble-like atmosphere elite sports teams are subject to when on tour. There is a notable absence of luxury, however. But that, surely, will also be to Eddie’s liking.

After a tour of the hotel, we meet the staff who successfully sold the hotel’s merits to Eddie: Jean-Francois and Chakameh.

Jean-Francois has been Le Touquet rugby club’s directeur sportif for the past seventeen years. A big man with a youthful, chubby face, he offers an easy smile as he tells us that like Eddie, he was a hooker, and that he bonded with England’s boss in a conversation about scrummaging. He also reveals that Eddie was particularly taken with how easy it would be for the players’ families to come and stay during the tournament.

It wasn’t all plain sailing in securing England’s residency however. Chakameh tells us that she’s had to reassure England in a number of areas. For example, the hotel will need to modify the size of its beds depending on how many XXXL players make the squad. Currently the likes of Courtney Lawes and Jonny Hill wouldn’t fit in to their beds (and those two aren’t likely to get any smaller between now and next September). They’ll also need to produce 40kg of ice per day for England’s physios and the strength and conditioning team, requiring the hotel to purchase two more ice-making machines. Initially, however, Chakameh was suspicious. “When they first told me they needed this much ice every day I thought ‘how much are you going to drink!?’”

Chakameh is a French-naturalised Iranian who speaks impeccable English. She seems like the type of person who can handle a mountainous workload and keep smiling. Which will be important next autumn as she’s due to be Eddie’s point of contact during the World Cup. A fixer for anything hotel-related. Does she know what she’s signed up for? “I understand how he works,” she insists. “I saw how he was, asking question, question, question.”

Our final night’s dining comes at Chakameh’s recommendation. Le Touquet is chiefly about fish and has some of the very best fish restaurants in France. Le Perard is one of them. A jaunty, bistro-style interior contrasts with its high cuisine. Dishes include oysters baked in cheese and champagne, lobster salad, sturgeon rilettes, an enormous fruits de mer platter, and for those not eating fish, there’s the Chablis-marinated snails, of course.

Le Perard is unlikely to be England’s kettle of fish, at least not before a game. Something stodgier, meatier – safer – would be better fare. Remember 1995 and the story of the All Blacks stricken with food poisoning? That supposedly came from eating fish 48 hours before the World Cup final.

For those of us able to take more of a risk, however, finishing off a trip to Le Touquet at a restaurant like Le Perard (and there are many similar joints in Le Touquet) rounds out a day rather nicely.

On the walk back to the hotel – England’s hotel – ice cream vendors warm the streets with fluorescent lightning, whilst armed gendarmes stand watch outside Brigitte Macron’s family house. Young children race around the streets, still with fishing nets and beach buckets in their hands. These days the nightlife in Le Touquet is an extension of its daytime: busy and family-focused. The night-time pursuits of the 1930s aren’t so in evidence, although the town’s casinos do seem to be doing a decent enough trade. However, Lille seems a safer bet for a big night on the tiles.

That is unless England win the damn thing next autumn. In which case, Le Touquet-Paris-Plage will become Twickenham-by-the-Sea for a week.

And that might be one heck of a party.