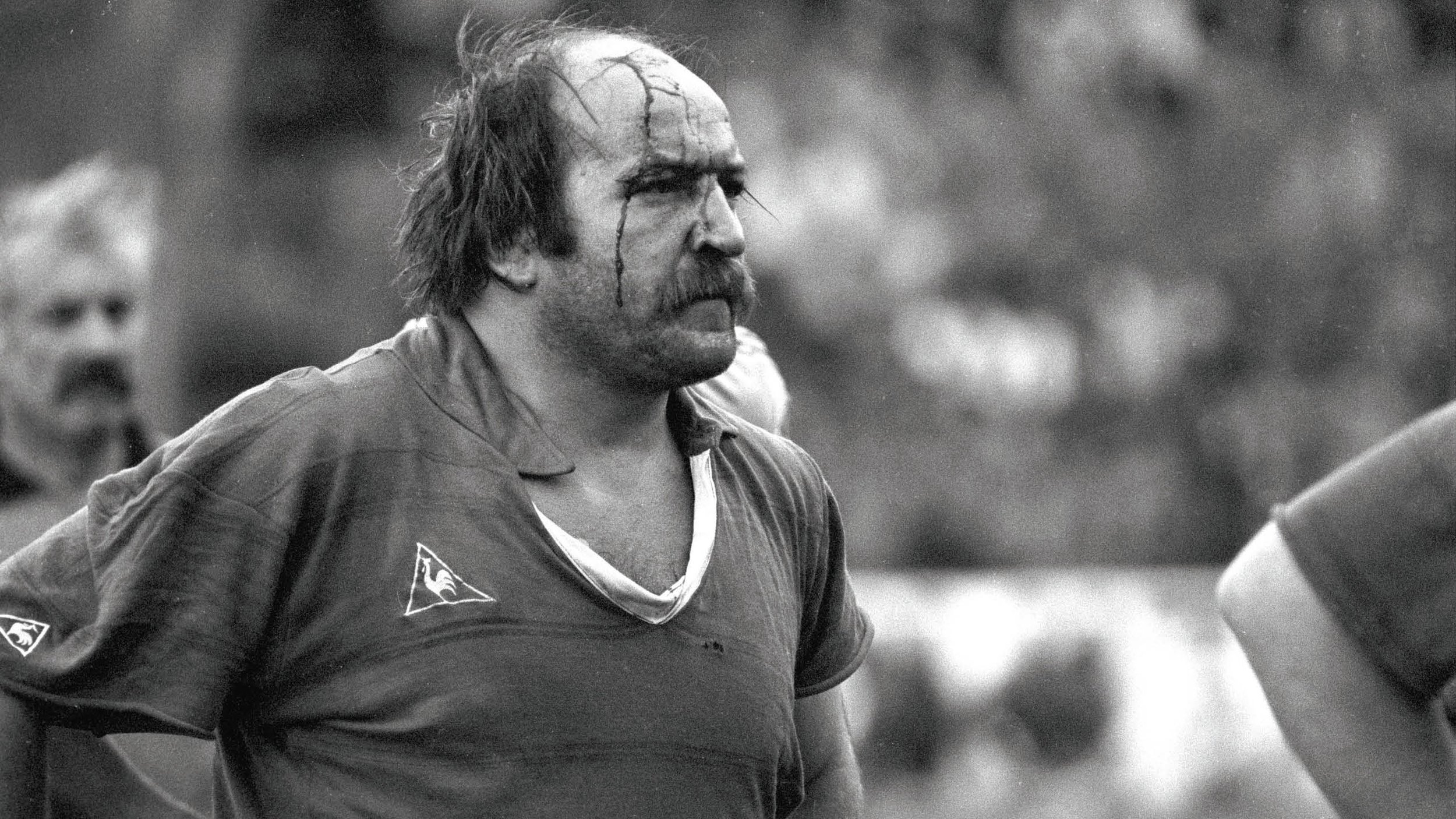

Armand Vaquerin

Armand Vaquerin left the bar, returned to his car and came back with a gun. He challenged the bar to a game of Russian roulette and, when there were no takers, he decided to play anyway. Moments later he was dead. At least, that’s one version of events.

Armand Varquerin would have turned 70 on February 21, 2021. He ranks among the greatest props ever to play for France, with a career peppered with stories of his brilliance and brutality on the pitch. It seems as if anyone who lined up alongside him or came up against him has a memorable tale to tell about Vaquerin.

And if he played hard, then he partied even harder.

But he never got to see his 43rd birthday. Vaquerin died on July 10, 1993. The cause of death was a shot to the head following a game of Russian roulette at the Bar des Amis in Béziers, in the South of France.

However, the exact circumstances which led to that moment remain unclear.

Several published versions state that the evening began at ‘Le Cardiff’ - a bar in Beziers owned by Vaquerin. The occasion was to celebrate the 20th anniversary of his first cap for Les Bleus.

It is then said that Vaquerin made his way to the Bar des Amis, a nondescript dive on the other side of town. A row broke out, Vaquerin challenged a man to a fight, then walked out to his car, brought back a gun, challenged that person to a game of Russian roulette and the other man promptly left the scene.

Vaquerin then laid down the challenge to everyone else and shouted, “If you bastards won’t play with me, I’ll play by myself!” He died moments later.

That version, however, is riddled with inaccuracies.

There was no such anniversary party. In fact, Vaquerin made his international debut against Romania on December 11, 1971. Furthermore, he died on the morning of July 10, not the evening.

But, more recently, a different, more complex and more detailed account has emerged, about a man who outwardly was the life and soul of the party but had an increasing number of personal problems.

And depending on who you choose to believe, Vaquerin either committed suicide, was murdered, or quite simply died by accident.

For example, according to one ex-player, it was Vaquerin’s party trick to be in a bar, pull out his gun and put a bullet into the chamber. Then, out of view from the onlookers, he would knock out the bullet, pull the trigger and live to drink another day.

So, did he simply make a mistake, or did he intentionally leave the bullet in the gun?

There is also the fact that Vaquerin was left-handed but the shot was fired into his right temple.

In an age when one of the most successful genres in modern culture is true crime, Vaquerin’s story has come to fascinate a new generation of would-be sleuths. More of which later.

But the other reason why the story continues to hold this fascination is that he was a genuine great of the game, adored in his home town. His death has only served to enhance his legend.

Ask any French rugby fan to pick their all-time best French team, and the 6ft, 16 stone loosehead would figure in most peoples’ starting XV.

Vaquerin only took up playing as a teenager but AS Béziers’ coach Raoul Barrière immediately recognised this was an exceptional talent in the making.

Barrière introduced training methods and a fitness regime that were instrumental in transforming the fortunes of a club that, before he arrived in 1968, had one French championship to its name.

Vaquerin soon became an integral part of Barrière’s team that had a stranglehold on the league championship throughout the 70s and the first half of the 80s.

He also won 26 caps for France. It would have been more, were it not for a knee injury sustained in 1980 and Vaquerin’s somewhat unconventional approach to conditioning.

He was philosophical about his international career, saying that “to be champion of France is to share the same joy with friends of your club and of your city, while it is a great personal joy to play for your country. For me, one is worth the other”.

But those appearances for Les Bleus during the 70s earned him a fearsome reputation in this country.

Scotland and British & Irish Lions prop Sandy Carmichael once described him as “a mental case”. Fellow Scot Alan Lawson recalled a story of Vaquerin looking down “incredulously” on prop Ian McLauchlan who had just booted the Frenchman twice in the face.

Yet he was so much more than just a hard man or pantomime villain. Vaquerin was an early prototype of the modern prop who could run with the ball and would weigh in with more than his fair share of tries.

And he was the ultimate team player. Former ASB teammate Michel Fabre said, “If we had a player who was injured, he was able to change position: he played on the left, on the right, he played everywhere.”

After winning ten titles in fourteen years with ‘Les Bitterois’, Vaquerin went out on a high, leaving the club in 1984 shortly after they had won what would become the club’s last championship.

His departure coincided with the team’s decline as Stade Toulousain became the dominant force in France. Eventually, Beziers would suffer the ignominy of relegation in 2005 and are still currently playing in the Pro D2.

His achievements are remembered through the Challenge Vaquerin tournament that began in the year of his death.

Challenge Vaquerin became a key pre-season tournament for clubs in France and the UK. Leicester, Northampton, Harlequins, Sale and Glasgow are among the teams who have previously taken part.

The ‘Friends of Armand’ organise occasional veteran matches. There is an avenue in Béziers named in his honour and a stadium named after him in the seaside town Valras-Plage. And on September 13, 2007, a statue of Vaquerin was unveiled at the Stade de la Méditerranée.

Alexandre Mognol was born and raised in Béziers. He grew up with Vaquerin’s story after his father, Claude, became a prop for ASB a year after the iconic prop had left the club.

Armand’s family were also regular customers in a flower shop owned by Mognol’s grandparents. “When you grow up in Béziers, you grow up with rugby and the story of her famous rugby team,” says Mognol.

“At the time, ASB were called ‘Le Grand Béziers’ and invented a revolutionary way to play, particularly with the forwards.

“And, of course, one of the team leaders was Armand Vaquerin. He holds the record of the most titled rugby player in France. He won ten ‘Boucliers de Brennus’ with Béziers and played in eleven finals. That’s huge!”

To have such longevity in the game is an achievement in itself. To do it consistently for the best team in the country is remarkable.

“This record will probably never be beaten,” adds Mognol. “Armand was powerful and brave as a player. For example, during the French championship final against Brive in 1975, he continued to play despite having a knee injury.

“I played rugby when I was a boy. Everyone knew Armand in Béziers. Every member of my family told me stories of Armand as a player and a little bit as a person, but not too much because I think I was too young to be told everything he did!

“His death by playing Russian roulette in obscure circumstances in a bar has added to his mysticism among Les Biterrois and a local kid like me.”

Mognol is now a Paris-based journalist. Four years ago he began exploring Vaquerin’s story and specifically the circumstances behind his death.

His starting point was a bar in Montmartre where Mognol was having a drink with his uncle, Stephane, who also once played for AS. They overheard two men talking about Jacques Mesrine – a controversial and divisive figure in French modern history.

Mesrine – pronounced Merrine – claimed that he murdered at least 39 people in a one-man crime wave that lasted for decades.

Known as ‘Monsieur Toute-le-monde’ (Mr Everybody) he evaded capture through changing his appearance. On the occasions that he was caught, he would find a way to break out of prison.

Mesrine also regularly taunted the authorities in magazine interviews and even had his memoirs published while he was still a wanted man. To his acolytes, he was the French Robin Hood who robbed banks and caused upset and embarrassment to the establishment.

They also claim he was unlawfully executed by police in 1979 following a showdown at Porte de Clignancourt, which is walking distance from Montmartre. To this day, there is still no official version of what happened.

One of the men in the bar said he witnessed the moment when Mesrine was ‘murdered’, while his drinking companion claimed he lived near the scene.

Then Stephane turned to Alexandre and said, “You see Alex, it’s like the story of Armand Vaquerin.”

Mognol adds, “My grandfather’s words have also fascinated me and have attracted my curiosity over time. He said and still says, ‘If you listen to the Biterrois, they were all in the bar when Armand died. You’d think that there were 50,000 witnesses! Each one tells his version.’”

Mognol went back to Béziers to explore Vaquerin’s life and death and the story became an eight-part podcast called Le Canon sur la Tempe, which, loosely translated, means ‘a shot to the temple’. He spoke to friends, family members, and a seemingly endless stream of characters who may (or may not) have been in the Bar des Amis on that day.

“In fact,” continues Mognol, “what is most strange and could sum up the plot of Le Canon Sur La Tempe is people who were not in the bar say they were there, and people who either were in the bar or were supposed to be in the bar say they were not.”

Mognol created a ‘crazy wall’, like the ones you see on TV crime dramas when they put up pictures of the key protagonists on a large board, and have arrows linking one to another.

A picture began to emerge of a man with a troubled personal life.

After he retired from the game, Vaquerin and his wife, Marguerite, worked and lived in Mexico. It was from there that they sailed across the Pacific to attend the 1987 Rugby World Cup when it was co-hosted by Australia and New Zealand.

It was in Mexico where some say his marriage began to fall apart. Vaquerin returned to Europe on his own before Marguerite later followed. They set up a business in Spain, but that didn’t work out, and all the while their relationship continued to go downhill before they returned to Béziers.

But there are also other suggestions that Le Cardiff was struggling financially, that he became increasingly paranoid, that he got involved in drugs, specifically cocaine, that he mixed with figures who had connections to organised crime and that he looked a shadow of his former self in the days leading up to his death.

There is also a story about a mysterious figure who was an ex-Legionnaire and was at the Bar des Amis on that day, and of a man who challenged him to that fateful game of roulette.

All the rumours, claims, and counter-claims, only serve to heighten the sense that his family will never truly get closure. Indeed, the Vaquerins didn’t receive a Procès-verbal; a police document that would have offered an official explanation of what happened.

What we do know is that the autopsy showed there was no trace of alcohol or drugs in his blood.

And what also comes through from the podcast is an overwhelming sense of loss from friends, family and former team-mates.

Among the people Mognol interviewed was one of Armand’s brothers, Elie. They played together in one of Béziers’ title-winning teams.

Elie also appears in Brothers in Arms, which was shortlisted for The Daily Telegraph’s Rugby Book of the Year in 2020.

It features the following quote from Elie: “Outside of rugby, he was a thunderbolt. He played and partied hard and would have got a lot more caps for France if he had focused more on his rugby! He would go out anywhere, any time and he would be out for days, sometimes weeks at a time, and he always burned the candle at both ends. But that was him. He loved life and we miss him greatly.”

Writing the book wasn’t so much a labour of love as a holiday of a lifetime for author David Beresford. Before becoming an entrepreneur and restaurateur, Beresford lived in France for eight years from 1986 to 1994 and played rugby in the Under 20s team for Chateauneuf-du-Pape.

After helping to float a company on the stock market, Beresford was able to fulfil an ambition and write a book about the golden era of French rugby in the 80s.

He got to hang out with his heroes, to wine and dine in bistros, bars and Michelin-starred restaurants with some of the greatest names in the history of Les Bleus including Jean-Pierre Rives, Serge Blanco, Philippe Sella, Patrice Lagisquet and Didier Camberabero. “The book is part dialogue, part travelogue, part chronicle. I want the reader to almost feel like they’re by my side when they’re reading the interviews, experiencing what I’m experiencing,” says Beresford.

It is a uniquely fascinating take on rugby in the 80s, but Beresford says no book on that era would be complete without at least one player from Béziers.

“I still think of the town as being a heartland of rugby, like Toulouse and far more so than Montpellier,” he says. “Billionaire Mohed Altrad (who failed in a bid to buy Gloucester) tried to put his money into Béziers, got turned away and put it into Montpellier which, for me, doesn’t really have a rugby culture. It’s more of a football city.

“Béziers is like Bath, Gloucester or Leicester, or Exeter right now. The soul of the town is about rugby, fraternity and passion. They care about the shirt. It’s not the most beautiful place but there are no pretensions either.”

He chose two Béziers players, both of whom died in tragic circumstances. Pierre Lacans was club captain, a gifted flanker, and died following a car accident aged 28. And then, of course, there was Vaquerin.

Beresford’s interviews were littered with anecdotes about Armand. “Laurent Pardo said to me ‘Armand, Elie, (and his other brother) Laurent went on a Club Med holiday in Sicily. After three days Armand hadn’t been to his room, and his bag was still next to the bar. He was just social, lovely, lively and wanted to party.’”

There is another story of a game against a Romanian team where Vaquerin was so brutal in his approach that the opposition walked off.

Beresford adds, “Jean-Pierre Rives said that when he played for Toulouse against Béziers ‘I used to get hate mail. My mother hated me playing at the Stade de Sauclières.’ The stadium is a hole, but it’s mythical; a symbol of Béziers’ greatness.

“Rives added, ‘They would always say “get Le Blanc”. But Armand would lie on me in the rucks and say “don’t move, they want to kick the shit out of you. But I’ll protect you.” Because that’s the kind of guy he was, right.’

“Vaquerin spoke with a lisp and was understated in the dressing room, but could dominate an opponent through his charisma and ability.

“He’s mythical. There’s an unconditional veneration that people have towards Vaquerin across France, particularly in Béziers.

“Like a rock star, his death is tragic and romantic.

“Elie didn’t want to talk about the death of his brother and the sadness in his eyes is obvious. But he told me that other players had said that allegedly he’d got in with the wrong crowd, the Toulon mafia. He got very paranoid.

“Elie is still very traumatised. They were very close, and you can see that he’s never recovered.”

Beresford likens Vaquerin’s passing to that of Christophe Dominici, the French winger who was found dead in a park near Paris last November. The cause of death was suicide.

“When they stopped playing, they couldn’t go and do a normal job. Where was the next adrenalin rush going to come from?”

If your French is up to scratch, or you have a friend who is willing to translate, La Canon sur la Tempe reveals a lot more about the life and death of Armand Vaquerin than anyone previously knew.

It poses enough pertinent questions about what happened in the Bar des Amis, and allows the listener to draw their conclusions, one of which is that Vaquerin took his own life.

After all, who would knowingly choose to play Russian roulette for the hell of it knowing they had a six to one chance of dying once they pulled the trigger?

It is also the story of a town where rugby reigned supreme.

Given Vaquerin’s status in Béziers, did Mognol wonder if digging up the past would result in a negative response to the podcast?

“Not so much nervous even though there was some risk. In general, the reviews were positive, and the podcast has been popular.

“I have received many messages, many thanks. One of his former team-mates even thanked me for learning more things he didn’t know about Armand. A woman told me that after listening, she felt like Erin Brockovich. Another man told me that he had listened to the documentary three times and visited the place where Armand died as a pilgrimage.”

As somebody connected to the story, who spent a year working on Le Canon sur la Tempe, how does Mognol see Vaquerin’s legacy both as a player and a person?

“A tournament, an avenue, a statue and a stadium have his name. His family members: brothers, sister, son continue to honour him.

“And today, I think most props in modern rugby play in a way that Armand was already practising in the 70s and 80s, with that combination of strength and mobility.

“Armand Vaquerin makes me think of George Best. It’s hard to have this kind of crazy, rock star life in today’s pro sport.

“Unfortunately, in the world of high-level sport, you can no longer find romantic personalities like Armand. There is nostalgia for these personalities. He is from another era, another time.”

Story by Ryan Herman

Pictures by Presse Sports

This extract was taken from issue 13 of Rugby.

To order the print journal, click here.