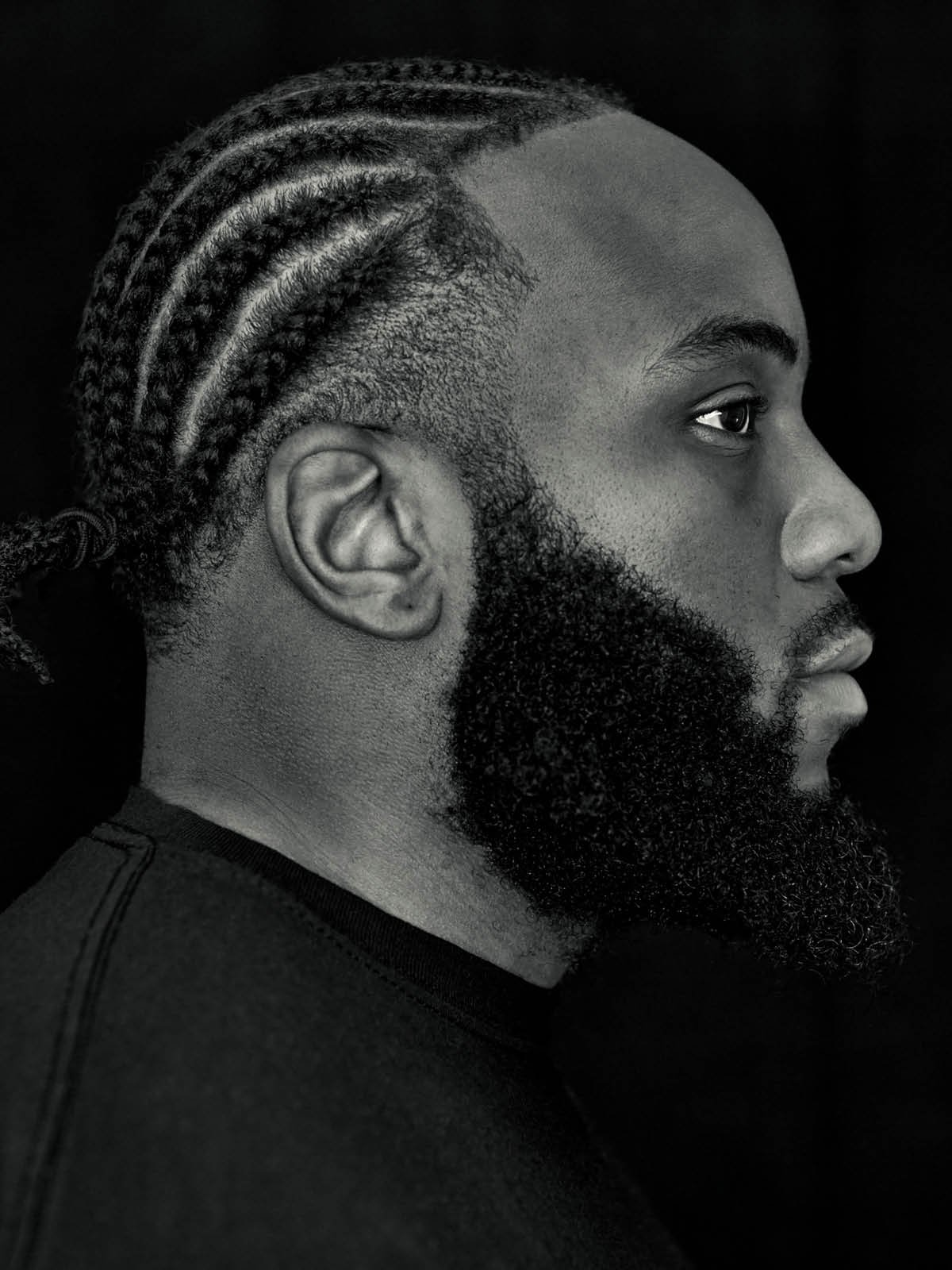

Beno Obano

At fifteen years of age, some inner-city kids are teetering on the edge of a life that can go one way or the other. Luckily for Beno Obano, who had started his rugby life as a six-try-scoring winger, he had no such choice – not with his mum Patricia on the case.

It was the sheep that first took Beno Obano by surprise when he rolled up at his new home in the grand estate that is Farleigh House, the sandstone country pile of Bath Rugby. “That was the maddest thing,” he laughs, turning the clock back six years to his arrival in the academy. “I was Snapchatting sheep because I hadn’t seen sheep like this before, just roaming everywhere. As you drive into Farleigh, there’s sheep on the other side of the training ground, and I was like ‘ah there’s sheep’ so I was posting all these stories of sheep and sharing with friends. Now I look at it, and it’s pretty normal to see sheep now...”

He’s adapted to country life, much as he has professional rugby life – first having to come to terms with not only sheep but also the stars that were now colleagues. “When I first came on trial at Bath I had Gavin [Henson] just outside me in training,” he explains, “I used to play as Gavin Henson on Rugby 08 – he had a star above his name – and I just thought that was wild.”

There was another, more significant difference, that Beno noted back then too. “I just thought black people were everywhere, especially in London, it’s pretty common place,” he admits. “Then you come to Bath and they’re not there. It’s also other things, like having the right barbers or not being able to get your stuff – like hair products and food. Bath had none of it, so that was a surprise.

“I never thought it was something different until I left and had to move out of London, I never saw it as the little black bubble it is.

“In contrast to the rest of the UK, southeast London, or even just London as a whole, is a bubble. But I love it there, it feels like home.”

Mum Patricia ‘was a good Catholic’ and so , like his brothers, went to London Oratory School. “She wanted us to go to a good catholic school, but they didn’t play football there,” says Beno, who’d spent his formative years dreaming of being a striker – or just behind the striker – for Chelsea. “I refused, but the headmaster called my mum saying, ‘we need Beno to play rugby’.

“At first my mum said, ‘but he doesn’t play...’ but then he told her ‘you’ve signed these papers saying he’s going to be involved in school activities’, and so I had to play.”

It wasn’t the worst thing that could’ve happened. Playing on the wing, he scored six tries in his first game. “I moved to prop the game after,” he explains. “At that age, the ball doesn’t get to the wing, people can’t pass, and I just wanted to be where the action was. I spent my games just picking up and going from the ruck all the time.”

Born in Camberwell, southeast London, Beno grew up first in Peckham, then in East Dulwich. “It was pretty peaceful, it was my community,” he says of his childhood home. “I thought life was always like that.”

“It’s weird,” he continues, “when you grow up and stuff happens in the area, you just think ‘this is just what happens’ and then you leave London and you realise it’s not like that everywhere else.”

What was he like at school? “I got into a bit of trouble,” he says. “I had a temper, which used to get me into a bit of trouble, but I wasn’t naughty – I didn’t get in trouble for talking in class or anything. But when I lose my temper, things happen, and I lost my temper a few times and got in trouble, in and out of school.

“There are instances where someone is looking at you, and you’re like ‘okay, is this an argument?’ and you get into a fight over nothing. You get into these disagreements, these arguments, these beefs, and that happens a lot in teenage years. But, I think that some of that stands you in good stead, for what I do now.”

Were you faced with knives? “I’m cautious when I’m talking about this sort of thing,” he responds, stopping his flow, “especially with journalists because journalists have a way of painting young black boys from London in a way that makes it sound like all of them were in gangs in the hood.

“But there were good people, there were wealthy people, there were what I see as middle-class kids involved in this, I don’t want to paint this other picture.”

Beno is keen to avoid the inner-city London gang trope that’s so keenly sought by the media when portraying sporting heroes from certain backgrounds. He wants to paint a truthful picture but is mindful that certain words prove to be key words of the searching media mind. He knows that words such as ‘knives’ and ‘black’ can often find themselves writ large in headlines, bereft of any context, and reinforcing an unwanted stereotype. “But we’re having a candid open conversation right now,” he begins again, “so I want to share a little bit, but I’m just cautious talking about that sort of stuff.

“Everybody in London was like that, it wasn’t personal to me, there was trouble everywhere.

“But then,” he continues, “you teeter on the edge in London. It can go either way. As much as you struggle, it’s your reality at that point. At fifteen or sixteen, you don’t know that you’re struggling, you don’t think you’re disadvantaged, you just think ‘this is life’, because that’s the way you’ve always seen it. And when you’re teetering on the edge of life, and there’s two ways it can go, fortunately I went the right way.”

Beno’s desire to be good at something was the difference, even if he didn’t know what it would be. “I was into music,” he says. “That’s why I first wanted to go to Brit school. I knew I’d be good at something, I didn’t know what it was.

“At sixteen I went to Dulwich College, and from that point on, I saw life just a little bit different.

“Everybody there was planning to go to Oxford, Cambridge, Durham, Warwick – they all planned to go to a top university and their dads are lawyers, QCs. That was when I thought, ‘well, I can do this as well’.

“Everyone tells you that you should want to be a doctor or lawyer, but when you grow up you don’t really come into contact with many top surgeons or QCs, so it drifts away.

“But when I went to Dulwich it was there – you did see these people, or at least their kids – and being there and not getting top grades, meant there was a level of shame if you didn’t achieve, so you sort of get dragged on with everybody else wanting to do well. It makes you want to succeed in life, and it’s shame that drags you there.”

Shame and his parents, of course. “Oh yeah, my parents were very strong on how well you do academically, that was the focus,” he says. “My parents are the biggest influence in my life and they’re the main reason why I play rugby today and why I’ve been half decent.

“They instil in you a certain drive and they expect certain things from you and that expectation from your parents is a big thing. You see it in the fact they sent me to Oratory, and the way they saw life – to move forward, to keep growing.”

Patricia and Frank [his dad] both arrived in England from Nigeria as teenagers, meeting and marrying in London, and having three sons, Tej, Beno and Suvwe. “When I talk about that age when you’re in London, and you can make those bad decisions it was because of my parents that I never made those terrible decisions,” he says. “They were quite strict, especially for my older brother. He had to face the brunt of my parents living in a Western society but coming from Nigeria – the way they deal with discipline and respect in Nigeria is a bit different to the UK, so all those things together, made it difficult on him.

“They were a bit easier with me though. They instilled that discipline and respect and expectation though – you didn’t want to fail them when you are presented with those bad decisions.”

Despite the tougher discipline, other aspects of Nigerian culture remain important to Beno. “It gives you a sense of identity,” he says, “it’s important to know where you come from, why you look a certain way – it explains why your parents talk a certain way with an accent, why your family are still there.

“It’s important to have that, and that’s why I make such an effort to understand the culture, and go over there whenever I can.”

While at Dulwich, Beno played for Middlesex, then was picked up by Wasps, who signed him as an 18-year-old, having spotted him two years before. Chris Lewis and Rob Smith had been his mentors and academy coaches at Wasps, but when they left and Matt Davies arrived from Saracens, a badly timed hamstring brought an end to his time. “I just don’t think he [Matt] thought I was going to take it seriously or be any good or whatever.

“At that point it went a bit funny,” he admits. “I didn’t know whether I was going to play rugby or not. I didn’t know, I figured I’d just go to uni.”

Mike Ford at Bath then provided a lifeline. “He said ‘if you get through pre-season, we’ll give you a contract’ – I got through it.”

And then began a life of hard-to-get hair products and roaming sheep. On the rugby side, things have been even more of a rollercoaster, as they often are at Bath. “When I started I was playing with Hoops, my debut was behind him in the scrum and now he’s my coach, that’s how long I’ve been there,” he says. “I’m sort of used to it now, but change happens at Bath – I think other clubs have been a bit more stable in their coaching set-up and I look at some pictures and I’m like, ‘oh gosh, there’s only two of us still here’, do you know what I mean?

“It’s part and parcel of the game I guess,” he continues. “I remember the first year and people were leaving, and you feel quite sad, but now you get used to it.”

And yet now, things do seem to be changing. “We’ve got a nucleous now that have been here for a while,” he says, “the likes of Charlie Ewels, Zach Mercer, Dunny [Tom Dunn], Tom Ellis – that’s the group that have come through together. And then obviously Tone [Anthony Watson] and JJ [Jonathan Joseph] too, they didn’t come through the academy, but they were young when they joined.”

The latter two are close friends of ’s, being his guiding lights through to adulthood. After doing everything he could to stay in the academy accommodation at Farleigh House, he was eventually ‘kicked out’ and after finding an initial home with Nick Auterac for ‘nothing rent’, he then went on to a similar deal at Watson’s house. “I stayed with him until I moved out a year or so ago,” he says. “JJ lived there too at one point and they were the best years of my life, honestly.

“I kind of took it for granted at the time, because that’s the first time you’re doing something, but living with those two, we just had the greatest time. I was

21, not playing as much, so could enjoy myself a bit more, and it was the greatest time of my life.

“I was becoming an adult at that point and even though Anthony is just a year older, he’d done so much more in his career, and JJ was four years older, so it was easy to follow those guys. They’d done a lot, they were England players, and I could learn from them. They guided me through early adulthood in a sense.”

All good things though? “Yeah, girlfriends man,” he laughs, “they ruin everything. JJ always had a girlfriend, but she had been at uni in Manchester, then Anthony got a girlfriend – who is now his fiancée – and she had to come and live with us.

“It got to the point, where it was five in the house, then JJ and his girlfriend left, so it was me, Anthony and his fiancée.

“I wasn’t on that much money so I was like, ‘I’m not going anywhere, I’m staying here as long as I have subsidised rent’. Then I got a new contract, played a little bit better, so I thought ‘yeah, probably time for me to get out of here now’. I had to fly the nest.”

By the time he flew the nest last year, he was established in Bath’s first team, and pushing for England, something he’s still doing now, albeit with considerable opposition in front of him. “Mako is arguably the best loosehead in the world, Gengy is very, very good, Joe Marler is a Lion and then you think of players that aren’t picked and you have the likes of Alec Hepburn, he’s been capped, and Ben Moony who has also been capped.”

Does he set England goals? “I try not to think about what I want to achieve in that [England] sense, it’s fool’s gold,” he says. “If I sit there and think about what I want to achieve, what if Eddie doesn’t feel you, and doesn’t pick you – you end up valuing yourself off someone’s opinion or selection.

“Some people have had very good club careers, they’ve got say 250 for their club, and then there’s another player who has got 50 caps for England but one player isn’t much better than the next.

“The only difference is that one person was liked by that coach and was able to have that career. I’d rather just get better and better. If I can do that, if he doesn’t pick me so be it, if he does then so be it, I can still achieve loads.”

That includes off the field too. Beno loves documentaries, so much so that he has become something of a critic. “I started to write reviews of documentaries and series, to share with people,” he explains. “People kept asking me for series and documentaries to watch, so I made a huge database of things I’d seen and wrote reviews for them.

“I made an Instagram account for it, colour-coded all the different types and told my friends about it.”

And the account is? “It’s not really up to date at the moment,” he says, deflecting us from the handle, “so it’s not in the best state...”

Instead, we have to suffice with a new documentary that he’s made himself, Everybody’s Game, now on a small streaming service called Amazon. “I just thought I had a good idea of what I wanted to see on TV, and the next thing you know I’ve got something on this big platform,” he says. “I wanted to broaden it beyond rugby people, because if I’d just put it on social, only rugby people would’ve seen it, so I got in touch with Amazon.”

Just a quick DM and you’re on with one of the biggest companies on the planet? “I have very good lawyers with good connections,” he says, “they were able to get the film in front of them, they watched it and liked it.”

The documentary tackles class and racism in rugby, with the talking heads including his cousin Maro Itoje, Ellis Genge and Anthony Watson. “I thought about this for a long time,” says . “Rugby has a class issue. People that play rugby, the general supporters of rugby, generally come from the same background and I just think sport is so good, it should be exposed to more people. I wanted to tell a story of people who aren’t from traditional backgrounds and how they came to play rugby, and the issues they faced, how we can improve those issues and make a documentary.”

A chance meeting with a production crew at a press conference, followed by a conversation over Instagram, led to Beno taking on his first director role, including being faced with an endless file of rushes [raw video footage] and transcriptions to plough through – fortunately, due to lockdown, he had time. “I remember, after doing the first draft and transcriptions, watching the rushes and thinking ‘this is so bad, I might have bitten off more than I can chew’. I didn’t know how to communicate to the editor what I wanted and he didn’t understand without me telling him. But I kept working at it, and it got better, and then we finally got it.”

When he talks of the video, he specifically says ‘class’ when race is clearly a big part of it. “I did specifically say class,” he says, “they are intertwined, but the focus is class, not race. And the reason the focus is on class is because it’s more important, because I also want the white boys who live in Tulse Hill to play or those Bromley boys whose dad played conference football but never even thought about rugby, yet they could tear it up as a ten if they did.”

It does arrive on the back of the Black Lives Matter movement, but that has had no impact on its timing. “I probably drove up the price a little bit though,” he laughs, “but no, I didn’t want it to coincide – I didn’t want the class part to get lost in the race side. Although, it might do now because everybody in the documentary is black apart from Gengey who is mixed race.”

The documentary is good. It’s thoughtful, insightful, with an easy humour that helps make a topic, that is sometimes thorny, approachable. Beno cares about what he does, just look at his Instagram, it’s carefully curated and not just a jumble of images thrown up without thinking.

He wants rugby to be bigger than it is. “It always feels like rugby wants to stay within its niche market,” he says, “it feels like some people in rugby believe, ‘it’s ours and we want to keep it that way;, rather than it going massive. We talk about that in the documentary and we speak about the media too, and how they portray players, not allowing it to grow.

“I think we need more people in rugby that are open to the idea of the sport growing beyond southwest London. If we do that it could be amazing as a sport.”

He brings us back to the early conversation about perceptions. “That’s why I was cautious earlier on,” he says, “because you say one thing and the media take this and runs with it and don’t paint the full picture, they take that little aspect and magnify and make that your whole character.

“It’s because young black people from London or generally people from any inner-city – it could be Birmingham or Manchester – are seen as being in gangs or trouble, that’s an image painted to the general public.”

The knock-on effect of this has meant Beno hasn’t always been able to be himself. “It means when I come into a rugby environment and I look exactly the same as these people – I talk exactly the same, I dress the same – it’s like ‘ah, this person must be problematic’. They associate how people talk, dress and act with being problematic or being in a gang, because they are in a minority.

“I went to Dulwich college, I went to a good school, but they don’t see that, they don’t see that you did well in your A-levels or that you’re doing a Masters, they just see the fact you’re another black boy from southeast London and you look the same as this other black boy who went to jail for however many years.

“They put someone in the paper whose face looks the same and they treat you the same, and that’s what I have found in rugby.”

Beno isn’t done with the documentary, he is also exploring other avenues beyond rugby, including a hip-hop-driven rugby festival. But music won’t be part of his own personal shtick. “I’ve tried to dampen this, but it doesn’t disappear,” laughs , when we talk of his ‘rap career’. “I saw a clipping the other day which said I went by a pseudonym called Sinny and I rap.

“I was like, ‘I don’t rap bro’. What happened was, at England camp, you have to introduce yourself and say something you’ve done, and I was ‘my name is Beno and I used to rap when I was at school’, and that was it.

“Eddie was like ‘we want to hear you rap’ and when Eddie gets on to something he keeps going with it, so I did a rap, and that was it, done.

“All of a sudden, I’m a rapper – you see what the media do?” he asks. “That’s the kind of thing I like to avoid, that’s why I don’t talk to the media much.”

But Sinny is a thing, as his social channels show. “I basically used to call myself Cynical, that was my nickname, my tag, when I was about ten or eleven, but I didn’t know how to spell ‘cynical’, so I spelt it S-i-n-i-c-a-l – that got chopped down to Sinny. And now I call myself Sinny, and name my companies after it too.”

We also need to talk about his cousin, simply because it’s a pre-requisite of all Beno interviews. “I did a recent interview and just said ‘I’m not talking about him’ – if Maro got asked as much about me as much as they ask me about him, then fair’s fair, but it’s not equal. Right now, it’s 90/10, if it gets to 60/40 or even 50/50, then I’ll be happy.”

You did use him in your documentary though? “You need to know where you get your money from though, innit?” he laughs.

Beno doesn’t miss a trick, but he also seems to be good at finding out what he’s good at, even if that started by chance, with rugby. “Rugby definitely just happened to me, it wasn’t a dream at all, but it gave me purpose,” he says. “I felt like rugby gave me a reason to be good at something: a focus. I didn’t want to think ‘I could’ve been something’, that was the biggest thing.

“I didn’t want to be talking about how ‘I could’ve done something’ or ‘I was good at this’ or ‘how good could I have been?’, I’d rather have just been good. So, I’ve spent a lot of time trying to be good, I’ve committed to it.”

That moment came when he rolled up the Farleigh drive and starting taking pictures of sheep. “I went to Bath and said, ‘I’m going to commit to being good at rugby’,” he says, adding, “and from that point on I started to take rugby seriously.”

Words by: Alex Mead

Pictures by: Han Lee De Boer

This extract was taken from issue 12 of Rugby.

To order the print journal, click here.