Danny Cipriani

When eventually Danny Cipriani stopped. When his life stopped going from game to game, club to club, trophy to trophy. When he was on his own, on the other side of the world, for the first time ever, he was hit by depression. Questions about his life he’d never thought or had time to ask, began to emerge to darken his days. Even for the gifted, life isn’t always easy.

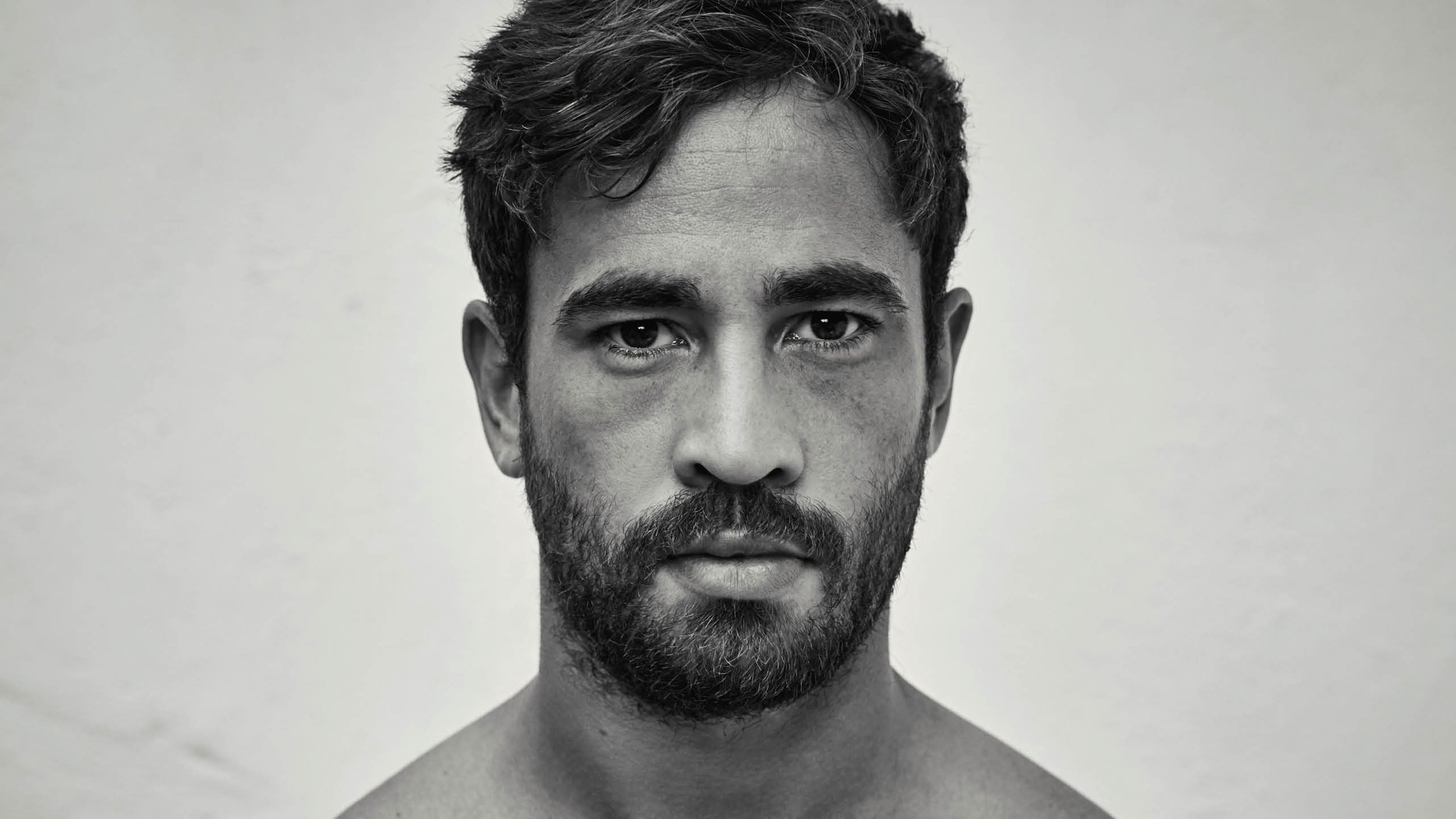

Danny Cipriani hasn’t done many fashion shoots of late. “I’d like to,” he admits, “but I’d just get too much grief.” As he poses in the courtyard with his shirt off, an office worker strolls into the frame with a freshly lit cigarette. He takes one look at the Danny’s ripped torso, glances down at his own less-than-ripped paunch, stubs out the cigarette and sheepishly does an about-turn.

Our photographer is a newcomer to rugby and is also taken by how good looking his subject is, “there’s actually something about Brad Pitt in him,” he says to his assistant, adding, “I think it’s the lips.” “Do you ever get that?” he asks Danny. “Erm, not really,” responds the Gloucester fly-half, clearly a bit embarrassed by the compliment.

After an hour or two of posing, being coaxed into every position and every expression, the shoot comes to an end, and Danny – never once demanding so much as a drop of water, or a break, despite being asked to face a wall for 15 minutes for one sequence, is as excited about seeing the outcome as the rest of us.

When we meet Danny, he’s in the papers, which doesn’t really narrow it down to any specific period of time over the past decade or so. Good or bad, Danny is the one rugby player everyone loves to talk about, he’s also arguably the only current player to truly transcend the sport. As big as the superstars of the game are in the minds of fans, few can genuinely call themselves household names in a way that Danny Cipriani can. In the absence of world cup-winners Jonny, Dallaglio and Johnno, ask a non-rugby fan to name a current player and Danny Cipriani will often be the answer. It’s because his every action, good or bad, is magnified, dissected, exaggerated (or underrated), and nearly always to an extreme, there’s no in between.

“Watching the media is like watching a fascinating social experiment,” reckons Danny. “I’m not talking about just when it’s linked to me, it’s everything. Look at how social media has driven everything from Brexit to Donald Trump. Obviously, I’m not linking myself to these types of people but the point I’m making is that it’s not necessarily the truth that needs to be out there, it’s just whatever makes good headlines and gets people interested in the story. Quite often the headline has got nothing to do with the story.

“I’m not sure where I’m going with this,” he admits, before adding, “I’m just saying it’s fascinating to see how these days everything has to be much more controversial or eye catching for people to pay attention. It’s all about shock factor no matter how big the story, people have to push the boundaries to get stuff going and it doesn’t matter how accurate things are.

“Ever since I was young, they’ve [the press] had this idea of who I am. You know, they say I’m a lothario who does this or does that, and so they have to create stories to build up this character. I have helped them with some errors and moments here and there, but it doesn’t translate to who I actually am as I person and how I treat people.”

Considering his reputation, when you actually look at Danny’s rap sheet, it’s thoroughly disappointing. Highlights include: getting punched by Josh Lewsey; staying out until midnight on the week of a match; taking a bottle of vodka from a hotel bar; getting hit by a bus – drink driving is perhaps the only serious one on the list. And then there’s Jersey, which we’ll come to later.

It’s true, in 13 years as a professional rugby player, there have been incidents, some of which could – and definitely should –have been avoided, but when written down in black and white, they don’t make compelling evidence for character assassination. He’s definitely more famous than infamous.

Bigger crimes in the eyes of some are, perhaps, not setting the world alight as a 20-year-old in two Tests against rugby’s superpowers, dating famous women, and training with a football club. “It’s frustrating for me when people say, ‘he’s had so many chances’. What chances are they talking about? I had one start for England in ten years.

“I know my skillset and what I can bring, and every time I’ve been given an opportunity at that level – whether it be off the bench for 10, 15, 20 minutes – I’d like to think that I’ve had an impact on the game in a positive way. There are obviously lots of things I can work on as a rugby player, which I’m continuing to do and I love that, I love being at Gloucester because there’s such a great challenge here.

“But, yeah, reading about all the chances is definitely the most frustrating thing I ever read, because I just don’t think I have really...”

Is that the worst thing you’ve seen written about you? “There has been so much, I can’t even pinpoint one thing,” he says. “There are times when you step back and think ‘wow’, is this really what I signed up for? You see the things that happen around you in a certain way and then you read someone else’s version of events and it’s completely different.

“That’s not to say that I haven’t made mistakes but sometimes it’s almost like a snowball effect and people are always thinking about how they can grab this and make it a bigger and more exciting story. It’s definitely been an experience.”

Jersey was also an experience, when his first pre-season Gloucester tour ended with Danny arrested. We don’t have to bring it up, as he does that himself. “The most recent thing was Jersey,” he begins, “and obviously I wasn’t happy with how things turned out.

“I think the whole incident was a misunderstanding more than anything else. It was misreported, which happens. I probably am still naïve in that respect even though it has been going on my whole career.

“I would have loved to change things, but it’s happened now, it’s not going to shape who I am. It’s given some people a chance to say what they want about me, but I can’t worry about it. I couldn’t be happier where I am in my life right now.”

With the present covered for now, we go back to the start. “When I was growing up, sport was always my shelter for everything,” says Danny. “My mum worked a lot so she was out a lot and I was always out too, playing sport with my friends. I never thought about what I was going to do when I was older because it was always going to be sport, I thought it was what I was meant to do.

“I was good at squash, I played for my county for the age group two years above me, I played for the South of England under-11 table tennis team, I loved badminton. I played cricket too, I loved batting, but I just couldn’t stand in the field all day, I’d get bored so I used to get into trouble for sledging – I was only trying to make it more exciting.

“I was probably best at football though, but my mum really didn’t want me to go down that route – she wanted me to be involved in a sport like rugby which was more inclusive, family orientated and had perceived better values and morals and all that sort of stuff.

“Reading came to see me for three games and in all three games I scored a hat-trick and they wanted to sign me up on YTS forms when I was 15. But my mum pushed me towards the rugby route which is why I moved school to Whitgift.”

Danny settled in quickly. “It’s a phenomenal school, and the headmaster, Dr Barnet, really liked me, which made a difference. And because they offered bursaries to all sorts of kids, it didn’t really matter how much your parents earned, or what they did. If you had the talent they would be inclusive and help you to achieve your goals. It was multi-racial, there were different religions, I just loved my time there.”

Academically, Danny got ‘good enough grades’, but by the time AS levels came around he was already on the books of Wasps. “By 17, I was training with the first team on Tuesdays and Thursdays, and so for the last couple of years at school my attendance was quite low – I was always back and forth at Wasps.

“There were loads of academic subjects I enjoyed, but I just always asked lots of questions: why are we doing this? Why is this going on? I wasn’t trying to be disruptive, it’s just the way my brain works, I’d rather know why something is happening, or has happened, and what the purpose of it was. For an example, if a coach asked me to do something, sometimes I’d ask ‘why?’ and coaches wouldn’t always like that, because to them it seemed like I was being disruptive. And I think sometimes they didn’t like it because they didn’t have an answer.”

One of those he often asked ‘why?’, was Brian Ashton. “I met him when I was 15 in the junior national academy and he challenged my way of viewing the game and it opened up everything; we used to have amazing conversations. We’d have classroom sessions with the best 20 players in the country aged from 15 to 18. You’d spend four weeks in the summer training at Bath Uni as a professional. He questions drills, he looks at how a drill transpires onto the pitch and asks, ‘is this just a drill for drill’s sake? You get that a lot in rugby, when all you end up doing is getting better at a certain drill and not rugby. Brian would challenge everything and made us think outside of the box.”

On the rugby field, right from the start of his time at Wasps, the lessons of Ashton paid dividends. “They had an unbelievable playing staff, Lawrence Dallaglio, Alex King, Fraser Waters, and the way they all embraced us was phenomenal,” says Danny. “I just remember when me and Dom Waldouck would run against the first team defence and we’d do things and cut them open and they’d love it, they loved that we were testing them. They’d encourage us and Shaun [Edwards] would always be telling us to ‘keep going, keep going’.

“That first season I came out of school they played me at full back,” continues Danny. “And I remember Shaun telling me that everything I needed to learn about rugby I’d get from watching Alex King – the way he runs and controls a game. From full back I could see how he controlled the game, his spatial awareness, how he managed the backline, what a leader he was.

“And that first year we had an unbelievable season. In my first year out of school we won Europe, then we won the Premiership and I just thought, ‘so, this is how it’s going be’. That’s how my life had been up to that point, every team I was in from under-11s onwards won everything and it just continued that way when I turned professional.”

Was that Wasps side the best you’ve played in? “Probably the most complete team,” he agrees. “The way we were coached too by Shaun Edwards, I’d sprinkle a few players in maybe – Willie le Roux at full back, Sam Jones, who had to retire, at six. Tommy Taylor, I’d maybe sneak him into the team too.”

A training session with England as a teenager – the summer before he was even technically a professional – had made international rugby part of Danny’s career plan, and he duly made his debut at 20, in the 2008 Six Nations. “It just felt like the next progressive step,” he acknowledges.

Although that step was taken, it was far from straight-forward. Two caps off the bench against Wales and Italy, a starting debut against Scotland that never happened after he was spotted out at midnight in match week (his mentor Ashton being the one to make the call), and finally a start against Ireland. A 33-10 win and one report that read ‘Danny Cipriani announced a new era and possibly saved head coach Brian Ashton’s job’.

It didn’t, not quite. Ashton was replaced the following April and while his replacement Martin Johnson gave him three starts the next autumn, Danny was frozen out. Then, in the summer of 2010, he decided to make his first major move, to Super Rugby side Melbourne Reds. Before that though, an arguably even bigger move, albeit a temporary one, to football. “I was looking forward to my time away in Melbourne,” he says. “But I had like five months to go, so I spent a lot of time doing football training. I trained with Tottenham for six weeks, I trained with QPR for a couple of weeks and then with MK Dons for a week, met a lot of good people and made a lot of friends through that time. It was a great experience – it was good being in a different sport and seeing how it runs.”

Was there a contract offer? “Possibly,” he says. “MK Dons spoke about it and there was stuff we were trying to weigh up. It would have been a risk on both sides but, you know, I had a contract in Melbourne and I thought I’d better honour it, I didn’t want to just turn my back on them.

“If I could have taken a year out and given it a go, just for a year, then I would have done it to see where it went, but at the time I was the black sheep of rugby so it wasn’t the best idea. I felt like if I did that there’d be no way back. In hindsight though I probably should have given it a go for a year.”

So lost in sport was Danny that, growing up, he never really thought about anything else, until he went to Australia. “I didn’t really have time to think about what was going on in my life because of everything I was doing,” he says. “It was probably only when I was 22 and I moved to Melbourne that I had the chance to reflect a bit and started asking questions like, ‘do you know what, where has my dad been? Why did this happen? Why was this, why was that?’ And when you start asking these questions you become a bit more conscious of what’s going on around you, instead of just living your life like a kid.”

Were you in touch with your dad? “I’ve been in touch with my dad the whole time,” he answers. “I spent a lot of summers growing up, going to Tobago and spending time with him. But, for me, in a sport like rugby which is so middle class, and is all about the values and family orientated, when all the kids have both their parents on the sidelines, and you don’t, it’s hard. And if you don’t feel truly accepted then it can be very hard to buy into those values. I think that’s the difference between rugby and football, I just feel like football’s more embracing of different characters in that way.

“When I was younger, people would just shun me for the things I did rather than look at the ‘why’ and try to talk to me to find out more.

“There were always people in my life that treated me as a person in my own right, people like Shaun Edwards or Brian, who are not only top quality, world-class coaches but great people – I still speak to them now every couple of weeks.

“I think it’s the coaches that aren’t quite sure of themselves that judge me, and I might react badly to them because, to me, it’s an authoritative figure who’s being disrespectful. I found that difficult growing up and I’d often react by putting a barrier up, and that would then stop me from having a good relationship with that coach or person.”

In Melbourne, Danny found the going tough. “It was a fun time and I enjoyed it a lot, I met an amazing group of people, but I was going through heavy depression at that stage of my life,” he says. “I look at it now and I was going through it day by day, training, playing, going out at the weekend, doing whatever you’re doing – you live in a bubble. But I was just getting more conscious of my mind. I was starting to question why I was feeling certain things, going through all sorts of emotions and I started reading lots of books to try and get to the bottom [of the depression] myself.

“Up to that point, everything had just been happening to me. It was, bang, you’re out of school, you’re going to play in your first game. Right, you’re playing, you’ve played it, you played well. Okay, now you’re in the Heineken Cup final, cool, you won it. I don’t really remember all these things happening. Every week there was something. There was no time to reflect on anything.

“It mostly hit me in the off-season,” he continues. “You’d find ways to try and deal with your triggers, training would be one, seeing your friends would be one, just ways of trying to forget and get out of your headspace. You just had to get used to sitting in those uncomfortable moments and realise that’s where your brain was at that moment.”

Did it start in Melbourne? “It was probably just before I went,” he says. “I had photographers outside my house every day, they were just so interested in what I was doing, where I was going, and I don’t think you can get used to it, not as a rugby player anyway. Movie stars find it easier to get used to it but I was just finding it all so overwhelming, and that was the feeling I had about everything.”

When things got too much in Melbourne, on and off the field, Danny decided to move back to the UK. It was here he met a man who would clearly change his life.

There’s a picture in one of the news reports after Danny was hit by a bus. While Danny looks as if the weight of the world is on his shoulders as he hobbles along on crutches, a grey bearded man is seen giving him counsel, it was Steve Black, a mentor to many over the years, including Jonny Wilkinson. “When I came back to the UK an old agent of mine said he thought I should go and meet Blackie. I didn’t really think I needed to because I’ve got lots of great people in my life,” says Danny. “I’ve got Margot Wells, the best fitness coach in rugby, I’ve got Shaun and Brian, so I have people I could turn to, but I respected my friend’s opinion and went to see Steve. We just sat and spoke for four hours and I just came out thinking, ‘wow, what an unbelievable human being’. We spoke about everything, and he understood my perception of things and now we speak all the time and I see him when I can, he’s a sensational human. He directed me onto the right path and taught me how to be an adult really.”

What’s often more surprising, yet telling at the same time, are Danny’s responses to certain questions. In the middle of a conversation about rugby, and his early days with the professionals, when you ask him if he’s ever been starstruck, you expect the answer to be a sportsman, but it’s not. Playing sport was always just what he did, and as long as he kept winning and doing well, it was obvious that he would start playing with better players. He could just as easily have been a professional footballer, cricketer or even table tennis player, so why would he be in awe of a rugby player? Hence the answer, after much thought, is Robert Downey Jr. “I was in Malibu having dinner with a group of people and he was sat next to me, we spoke a bit.”

What did you talk about? “Lots of things, he doesn’t know rugby but he knows about contact sport and he’s into his martial arts and things.

“I wouldn’t say I was starstruck but I love Iron Man, so I was like ‘I’m talking to Iron Man!’ I didn’t know much about his past but then I researched and saw what he’d been through, and all the ups and downs and look where he is now. It did make me think that, on those days when it feels like there’s so much pressure from the media, it’s ultimately just another day.”

In a similar vein, when we talk about his post rugby career, while coaching is on his radar, the first thing he mentions is mentoring kids, but footballers, not rugby players. He’d like to mentor young players on how to be a professional. “It gets lost in all the stories out there about me, but I do a lot of work on the mental side of the game, as well as the physical, to ensure I can play at the highest level.

“And I think I can be a sounding board for those types of young kids because I think they go through a lot, you know. A lot of them have single parent homes. I grew up on a council estate and there are a lot of things I can relate to on that front, it does make it a bit more difficult coming into the professional sports environment from that side.”

Other things. We talk before the autumn Tests and don’t know if he’s played his last England game or not. And if he has? “I would just think that was my story, man,” he says. “When I’m done in the next couple of years, I’ll just know that I’ve given it my best shot, if coaches in those times have felt it difficult to get to know me or felt like I was challenging, then maybe we’ve all got some learning to do.”

Ignore Jersey, ignore hotel bars and buses, Danny Cipriani is definitely a grown-up. His summers are no longer spent on lads trips away, but in America with big-wave surfer Laird Hamilton and his wife Gabi, a pro volleyball player. “I train with Laird every summer,” explains Danny. “I didn’t know much about him before, but a good friend of mine lives over there and introduced me to him five years ago.

“I used to go to LA every summer and party in the off season, but ever since I met Laird and Gabi they’ve treated me as one their own, it’s been life changing really. I stay with them every year for the whole summer. They’ve got amazing kids too, Reece and Brodie.”

His influences these days seem a world away from the red top fodder of his youth. His closest friends are still those from his school days, and even his agent Oli has been a good friend since childhood.

Having grown up in a family of two with his mum, he’s now got extended family everywhere and is a dead cert for following the family route himself. “Yeah, I’d love to,” he admits. “But I guess that’s the future and I’m just trying to live in the present – there’s so much to enjoy right now.

“I enjoyed that shoot, it was cool,” he says, repeating his earlier sentiments. “I haven’t done stuff [photshoots] in a while because, when I do, people view me as not being serious about rugby or whatever – there are so many ideas written about me. People can say whatever they want to say about me but, like I say, it’s all just a great social experiment.”

Words by: Alex Mead

Pictures by: Han Lee De Boer

This extract was taken from issue 4 of Rugby.

To order the print journal, click here.